OldSpeak

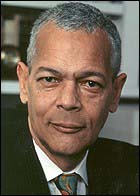

A Powerful Figure: An Interview with Civil Rights Activist Julian Bond

By John W. Whitehead

January 20, 2003

|

"Martin Luther King was a universal leader," says Julian Bond, chairman of the NAACP. "He wasn’t an African American leading other African Americans. He was a universalist. He believed in the common humanity of all, really a giant, if not the giant, figure of the 20th century."

Bond himself could rightfully be called a giant. As a student at Morehouse College in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1960, he co-founded the Committee on Appeal for Human Rights, a student civil rights organization that worked to desegregate Atlanta’s movie theaters, lunch counters, and parks. During his tenure with the group, Bond was arrested for sitting-in at the then-segregated cafeteria at Atlanta City Hall.

At the same time, Bond also served as the communications director for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), heading the organization's printing and publicity departments, and working in voter registration drives in rural Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Arkansas.

In 1965, Bond was elected to a one-year term in the Georgia House of Representatives, but members of the House voted not to seat him because of his outspoken opposition to the war in Vietnam. Bond won a second election to fill his vacant seat in 1966, and again the Georgia House voted to bar him from membership. He won a third election—this time for a two-year term—in November 1966, and in December the U. S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously that the Georgia House had violated Bond’s rights in refusing him his seat.

During this particular struggle, he was publicly backed by Martin Luther King, Jr., who had briefly been Bond’s professor at Morehouse. "He led a march on the state capitol in my defense," Bond says. "He was also a plaintiff in the lawsuit that ultimately put me back in the Georgia legislature. He was extremely supportive." Bond also joined the Georgia Senate in 1974, and when he left the office in January 1987, he had been elected to public office more times than any other black Georgian, living or dead.

When the Southern Poverty Law Center was founded in 1971, Bond became its President (he is still President Emeritus). In addition, he was host of "America's Black Forum," the oldest black-owned show in television syndication, from 1980 until 1997, and is still a commentator on the show (he also hosted an episode of Saturday Night Live in 1977).

Currently a Distinguished Scholar in Residence at the American University in Washington, D.C., and a faculty member in the history department at the University of Virginia, Bond continues to be outspoken. At this summer’s 93rd annual NAACP convention, he attacked President Bush and Attorney General John Ashcroft for their civil rights/liberties records, accusing Bush of dealing in "snake oil" and calling Ashcroft "a cross between J. Edgar Hoover and Jerry Falwell." "There is a right-wing conspiracy," Bond told the assembled audience. "And it is operating out of the United States Department of Justice."

On the eve of Martin Luther King Day, Bond spoke with John W. Whitehead about the slain civil rights leader, his own legacy of activism, and the state of race relations in present-day America.

OldSpeak: As you were growing up, you saw the times changing. What radicalized you?

JB: I don’t think I was ever radicalized. I think I was mainstreamized. I was raised in a home by parents who led my sister and brother and myself to believe that we were equal to anybody else. So I began life early on believing I could do anything I was smart enough to do. I could go anyplace I was vigorous enough to go; the world was mine. And while I knew there were going to be obstacles because of race—that was also a part of household discussion—I was taught they could be overcome.

What about the Rosa Parks situation? Martin Luther King? Obviously, they had an impact on you.

They did. But I was 15 when Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on the bus, and I don’t think I knew about it immediately. I was living in Pennsylvania, and this was in Alabama–many, many miles away. It didn’t break out of the Montgomery news media until 1956. The bus boycott continued on for several months before the rest of the world really knew what was going on or knew there was a person named Martin Luther King involved in it. But as I began to know and as I absorbed what my teachers were telling me in the schools—the segregated schools both public and private that I attended—and as my parents talked to me about their lives, their experiences and notable black figures and because of where I lived, I became conscious of what was going on around me. I grew up on a college campus, and that was a location where prominent black figures were in and out continually. So I had exposure to the prominent people of the day, much different than that of the typical young person. It all came together and prepared me for the civil rights movement that was coming, long before the civil rights movement of the 1960s came along.

You had to realize that the world, when it looked at you, saw a radical.

Yes. That has been somewhat hard for me to understand in part because the whole political debate has shifted to the right. And while it’s a relatively recent phenomenon, it began years and years ago. So if you used to believe there was a left, a right and a middle in American politics, all that shifted to the right. What used to be on the right has now moved over further right, what used to be in the middle is now where the right used to be and what used to be thought of as the left is now occupying the middle. I have always thought, although I think I hold some views that some people would consider radical, that I’ve been a mainstream kind of person. I’ve wanted to go right down the middle, and I guess that’s the way we see ourselves as opposed to the way people see us.

You’ve always been outspoken. In the early ‘60s, you even criticized Martin Luther King.

Yes. I grew up in a movement tradition that was hostile to the idea of the charismatic leader, the great figure who swoops in from out of town and says a few words at a mass meeting or leads a march and then swoops away and the whole situation is changed. I was taught early on to be hostile to that idea. I really think that idea was detrimental to the development of a democratic movement.

Is that how you saw Martin Luther King?

Oh, very much so. Not so much because of King himself but because of the circumstances in which he found himself. He was surrounded by people who were nothing but "yes" men and said yes to everything he said. He almost never heard any real critiques of what he was doing, although he did hear some.

Do you think that, if you had been one of his assistants, you would’ve criticized him?

I probably would’ve been one of the "yes" men, taken up by this charisma.

He was charismatic.

A powerful, powerful, powerful figure. He taught me. You know, a lot of people say I was a student of Dr. King, but actually he only taught me one time.

At a philosophy seminar at Morehouse.

That’s right, and I was one of a small band of students. I’m one of the few people in the whole world who can actually say I was a student of Martin Luther King.

What did you think of the course he taught?

I’ve talked to my classmates, the ones I can track down today, and almost none of us remember anything that was taught in the class. I do remember that he co-taught the class with the man [Samuel Williams] who had taught him philosophy when he had been at Morehouse. This man probably knew much more about philosophy than Martin Luther King did, although King knew a great deal.

One of King’s strengths was that, when it came crunch time, basically he was there. He came to your defense when the Georgia legislature wouldn’t seat you because of your opposition to the Vietnam War.

Oh, absolutely. As we’re talking, I’m looking at a picture–a photograph hanging on my wall of he and I standing at a ballot box. We’re casting votes for me–at least, I know I voted for myself. And he told me that he voted for me in that disputed election. He then led a march on the state capitol in my defense. He was also a plaintiff in the lawsuit that ultimately put me back in the Georgia legislature. He was extremely supportive.

By that time, had you changed your mind about him?

A little bit, yes. And it wasn’t just the support that made me change my mind. It was the realization that he was, in some ways, a captive of the movement that he was leading and that it was bigger than Martin Luther King himself.

King was a Christian minister. Ralph Abernathy was a minister. There was a lot of Christian influence, religious influence, on the civil rights movement. Do you think the movement was essentially religious?

I would say that, for most of the participants, that’s absolutely the truth. However, we tend to think that every black minister in the South was engaged in the movement. In fact, only a small minority of the black clergy was involved. They were then, and to some extent are yet, a generally conservative population. That is not to say conservative in the standard Democratic/Republican, right/left terms but conservative in that they are opposed to any aggressive action outside of the norm. Many of them denigrated what King was doing. This is particularly true in Birmingham and elsewhere where he appeared. Thus, it’s a big mistake to think that every black minister from every pulpit was leading the charge. King and Abernathy and the small group around them were very much a minority. But religion was an overwhelming motivation for most of them.

There was a lot of dissension in the civil rights movement among African Americans.

Oh, yes, an awful lot.

Was it egos?

It’s important to note that there was very little dissension over goals. There was a lot of dissension over means. But the dissension over means was restricted to what’s the best way to knock down these walls tomorrow morning, as opposed to can we wait some time for things to change, for conditions to shift? So it’s not really a debate over whether to knock down the walls with nonviolent force as quickly as you can this morning or wait until this afternoon. I mean this in the sense as opposed to a real debate over whether or not this ought to take place now or six months or so in the future. So there was debate. A lot of it was ego driven. We have to understand that whether they are ministers or non-ministers, whether they are religious or irreligious, they are first of all people. And like all other people, they have differences of personalities, of strategy, of tactics and they are going to disagree. The fact that they agreed as much as they did is a real phenomenon.

Government officials at the time were obviously very nervous about the activities of King and the civil right movement, as well as the activities of university students. Anarchy is a word that comes to mind. In your recent speech at the NAACP Convention, you said that the FBI tried to disrupt the civil rights movement. They not only wanted Dr. Martin Luther King discredited, they also wanted him dead. Are you intimating that the government was involved in Dr. King’s death?

No, not in the actual act of killing him. But prior to that, they had sent King a tape recording of people sitting around telling ribald jokes, intermixed with the sounds of a couple having sex. This was accompanied by a letter to King suggesting that he commit suicide.

Was this the FBI?

The FBI did this. J. Edgar Hoover did this. The intimation was that unless King committed suicide, this tape would be made public and he would be revealed as a morally degenerate person. So the government tried to urge King toward suicide. They tried to get him to kill himself. This actually occurred, and it is well documented. That’s why I think it’s good for Americans today to have some healthy skepticism toward police agencies and police tactics. While these are forces we badly need in society, they are also forces that we have to look at with some skepticism. We always have to ask if it’s necessary, if it’s the right thing to do. Sometimes it is, and sometimes it isn’t.

There’s a controversy within the King family that maybe James Earl Ray wasn’t the one who killed King. There are conspiracy theories that King was shot by the government just to get him out of the way because they were afraid of his power. Do you subscribe to any of that? Do you have any concerns about it?

No, I don’t. I haven’t seen any evidence that anybody was involved in this besides James Earl Ray and perhaps his brother. In order to commit a successful crime, you need the means, motive, opportunity and the victim. James Earl Ray had all those things. I have never seen any convincing evidence that there was anyone else involved in the murder of King.

How did the murder of Martin Luther King affect the civil rights movement?

It was like a hammer blow. This is true, whether you believe the movement ought to have one leader or not. And, of course, I didn’t think it ought to have one leader. But whether you believe that or not, he was the leader.

He was the Moses.

Yes. And to have your Moses struck down, with no apparent successor, was just a crushing blow because it meant that the person around whom most people could rally had vanished. He had disappeared. So there was nothing you could do about it.

When King was killed, I was a student at the University of Arkansas and had gone to a local hangout that was very crowded. All of a sudden there was a loud cheer from a group of all-white students, and I asked what was happening. A guy jumped on the table and said that Martin Luther King had just been shot and killed, and the room broke out in applause. I was stunned. This, of course, highlights the obstacles you were fighting then and probably still are today. Is there a huge segment of the population that still believes like this?

I don’t know if there’s a huge section of the population, but I do think there’s a sizable one. I don’t know how large it is, but there’s a section of the population that believes the movement should not have happened, that its successes were wrong successes and that the leadership was bankrupt and corrupt.

Do you think there was corruption in the leadership of the civil rights movement as well?

There was occasional corruption. As I said a moment ago, we’re dealing with people and people do certain things. Just look at the CEOs of major companies engaging in corrupt acts. We know people in government engaging in corrupt acts. Look at the Catholic Church and its present travails. No section of society and no part of society are immune from evil. So sure, there were people who misbehaved, both on a very small and on a large level in the civil rights movement. Generally speaking, however, it proceeded along with principal leadership who had high moral standards, who conducted themselves in the best possible way in every circumstance. But you would be foolish to say there weren’t some corrupt people in it.

There were allegations by the Black Panthers during the late 1960s and early 1970s that the police were trying to wipe them out. Several Panthers were shot and killed in Chicago, students who led nonviolent protests were attacked and your offices were raided. Do you think the government at that time was trying to stamp your movement out?

Oh, absolutely. J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI had a program, COINTELPRO, in which they targeted several groups, including my own Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the Black Panther Party and others, and engaged in all kinds of despicable tactics–break-ins, wiretappings and the like. They even used informers who, by way of disinformation, carried tales back and forth among the different groups and created bad blood between various organizations, some of which resulted in shootouts. We know that the FBI, and to some degree the local police forces, were actively engaged in disrupting the movement–doing all they could to tarnish and discredit it. We know these abuses happened. What is surprising is that so few people turned out to be victims of this awful, awful conduct.

The times have obviously changed. Many people today believe that discrimination on the basis of race is wrong. In fact, even an illusion to racially motivated ideas can create a fiasco. We see this with Trent Lott. What do you think the significance of the Trent Lott situation is?

First of all, it gives the Republican Party an opportunity to examine its behavior over the years, at least from 1964 to the present. The Republican Party has traditionally played the race card; that is, it has made coded and veiled appeals to the portion of the population that still believes in white supremacy and segregation in subtle, overt ways. These range from appearances at Bob Jones University, such as that by candidate George W. Bush in 2000, to refusing to speak out against displays on public property of the Confederate flag. The man elected governor of Georgia, Sonny Perdue, another Republican, won that election largely because he promised to restore the Confederate flag to a place of prominence in the Georgia state flag.

So there are a lot of people out there that still have not changed?

Yes. But the Trent Lott crisis gives the Republican Party a chance to examine itself and to ponder whether it’s going to continue to appeal to this small section of its base that embraces the Confederacy and is hostile to civil rights laws. The Republican Party has to decide whether it’s going to try to expand its base, to reach out to people who traditionally have not been Republicans, and become a better party. It will be interesting to see what they decide.

Do you think Trent Lott is a bigot?

Oh, yes. Oh, sure. I mean, here is a man who in almost every public act of his life, from the early 1960s until recently, was doing things that the most charitable person would say were at least vaguely racist. Look at his record. He opposed the integration of Old Miss. He opposed the integration of his fraternity. He worked for one of Mississippi’s most segregationist congressmen. He ran for office, and the first bill that Lott introduced was a bill opposing school busing. Lott amassed a record in Congress that was in rigid opposition to mainstream remedies for discrimination. Then in the late 1990s, he began an association with a white supremacy group. Lott spoke at their meetings, he endorsed their goals and he hosted their leadership in the Senate office in Washington. Then he said he didn’t know anything about them.

Politicians seem to have convenient memory lapses.

And in 1980, Lott made this awful statement about how he wished Strom Thurmond had won. Then he made it again two years ago. And then he made it again at Strom Thurmond’s latest birthday party. So taken together, the obvious conclusion is that this guy is a racist. If he’s not a racist, it’s even worse because he’s adapting an attitude in order to please some strange constituency.

Or he’s incredibly stupid.

Yes, that could be true, true.

But like a lot of old-line bigots, hasn’t Lott changed? For example, Representative John Lewis (D-GA) said that forgiveness is the spirit of the civil rights movement.

I think you might be able to forgive an incident and a statement. But what Trent Lott is asking us to do is to forgive his whole life. And that is difficult to do without some real repentance, at least for me. I want to see how tomorrow’s Trent Lott will be different from yesterday’s Trent Lott, both in words and in deeds. If I am shown that, then I’m willing to welcome him back into the family of civilized people.

Do we not face a crisis in some of these situations in terms of the right of people to speak? Our First Amendment dedication to free speech seems to be hanging in the balance. It ranges from the Trent Lott ordeal to the recent situation at the University of Virginia where three white students came blackfaced to a Halloween party. Prominent African Americans spoke out and urged sensitivity training, in other words, forcing the students into deprogramming seminars. Do we really want to force white students into these kinds of programs? Aren’t we in danger of suppressing what used to be known as free speech? And don’t we want people who are racist speaking out so they’re visible? Or do we want to force them underground?

I would rather have them speaking out. I would rather know who they are and where they are and what they’re up to. There is always a conflict between free speech rights and the rights of others not to be offended.

But doesn’t free speech always offend?

Oh, sure it does. If someone violates my right to not be offended, what recourse should I have and what recourse should the larger society have? Trent Lott, for example, has a perfect right to say stupid things if he wants to. But we ought to also have the right to challenge him. And his colleagues in the Senate ought to have the right to say, "You can say whatever you want, but you can’t say that and hold this prestigious position." So it’s a real balance between letting everybody have their free speech rights—which ought to be our goal and our desire—and also finding some way to repudiate hateful speech.

With other free speech.

Yes, but sometimes the other free speech never speaks as loudly as the hateful speech.

But do you really believe that those kids coming blackfaced was hateful speech—or was it a mistake?

It was probably ignorant speech. I don’t know them, and I don’t know what prompted this. But this happens so often. It happens over and over again. And you have to ask yourself, what’s the motivation for this? What’s the thought behind this type of activity? Why do white college students do this time and time again? What’s in it for them? What are they getting out of this? I don’t know. I wish somebody would study this or interview them or investigate the motivation behind it.

But there’s a problem. There’s so much criticism that they go underground and you can’t talk to them. I’d like to interview them but can’t find them.

We know who did it. We have their photographs, although they’re typically in blackface. But we know the fraternities that did this in Alabama and elsewhere. We know who the people are who are doing it. Some social scientist ought to track them down and, if they’re willing, ask, "What prompted you to do this? What were you thinking about when you did this?"

There’s a case before the U.S. Supreme Court, Virginia v. Barry Elton Black. It’s the cross burning case, which I’m sure you’re familiar with, where the Imperial Wizard of the Keystone Knights of the Ku Klux Klan burned a 30-foot cross on private property during a Klan rally. Is this free speech?

I don’t know. I’d like to believe I’m a big free speech advocate. But I’m certainly not a lawyer, and I’m not sure I really understand all the legal nuances of this case. I was very, very surprised to hear Justice Clarence Thomas speaking out about this. I’m extremely sympathetic to what he had to say.

It’s very rare for Thomas to speak out.

Very, very rare. I wish I had been there. I could have told my grandchildren. I think cross burning is different, and I’m not sure I can articulate why it’s different. I know why it’s different. It’s like pornography or what someone said about pornography, rather.

You know it when you see it.

Yes, you know it when you see it.

Well, the difference between cross burning is that it has a definite intention to intimidate, does it not?

Yes, an intention to intimidate a certain class of people in a way that other sorts of things don’t.

How would that be different than a white supremacist on the street corner in New York City, who has every right to be there? When he sees black people walking by, he says, "I don’t like you because you’re a" and uses the "N" word or some other derogatory term. And then he says, "This is free speech. I have a right to say this."

I don’t know. I grant you that could easily be called free speech. But I don’t know. I’m not a lawyer, and I don’t know all the legal nuances.

Let me put it this way. You’re a lawyer and Barry Elton Black—the defendant in the cross-burning case—comes to you and says, "Hey, they’re going to sink me. I need my free speech defended." Would you help defend him?

Yes, I believe that lawyers have a responsibility to defend anyone, no matter who that person is. So it doesn’t matter how objectionable they are as human beings or how objectionable what they’re saying is or how heinous the crime is they’ve been accused of or how dirty the words are. I think lawyers have a responsibility to represent anyone, no matter who that person is.

Let’s talk a moment about another area of concern in recent years. That is the threat to our constitutional liberties, mainly because of the Bush administration. Shortly after 9/11, George W. Bush pushed through the USA Patriot Act, which is probably the most pervasive and invasive piece of legislation ever signed into law by a president. If the USA Patriot Act had been at J. Edgar Hoover’s disposal during the civil rights movement, could he not have almost wiped the movement out?

Well, of course he could have. You’re absolutely right that we’re facing real threats to our liberties now under the cover of making ourselves more secure against terrorism. It’s really frightening to see that people in the Bush administration, particularly Attorney General Ashcroft, have so little regard for the rights, for the privileges, for the safety and security of Americans that they would attempt to lock people up without trials, to put them away in camps without lawyers. It’s just a long, long list of deprivations.

Or as you called Ashcroft, J. Edgar Ashcroft.

Yes, I did, and well deserved, too. They’re cut from the same cloth.

Nat Hentoff has said that Ashcroft could not pass a test on the Bill of Rights.

No, I’m sure he couldn’t.

Let’s talk about the potential war with Iraq. Everyone knows your war record. You’ve been vocally anti-war since the Vietnam era. Now you have George W. Bush, a war-hawk president who, no matter what happens, no matter how Saddam Hussein tries to appease America, seems to want a war.

Yes, I think it’s clear from the afternoon of 9/11 that the Bush administration wanted to go after Saddam Hussein.

Why? Do you think it’s the lust for oil?

I think it’s a combination of things. I think it’s the father’s unfinished business. I think it’s a political diversion from domestic concerns. It’s all of these things and perhaps even more that we don’t quite realize. I want to see some convincing proof, number one, that Saddam Hussein is connected with 9/11. But there’s no proof of that. And number two, that Hussein has weapons of mass destruction. But there’s no proof of that. So what’s the rationale here? What’s the reason here? And this notion of preemption is a radical departure from the way we’ve conducted ourselves in the past.

It’s anti-democratic government.

It is. It’s dangerous, dangerous.

It’s what you’ve labeled imperialism.

It’s the worst kind of behavior for a country that fancies itself to be the leader of the free world.

You’ve been vocal in your opposition to George W. Bush. In your speech at the NAACP Convention, you said, "This is a vast right-wing conspiracy. It’s operating out of the U.S. Department of Justice, the Office of the White House Counsel and the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights." The question is: Is it really a right-wing conspiracy or is this just the way that governments operate? They maintain power; they capitalize on issues and problems. Politicians, as we know, will do almost anything to stay in power.

Well, I think it is a conspiracy in the sense of several people acting together to advance a common cause.

Aren’t they fairly open about what they’re doing?

You could say that’s a description of government itself. But, in this case, I was talking about the Federalist Society and the enormous influence that group has over aspects of the Bush administration.

Well, obviously Bush is part of it.

Yes, indeed. Well, he couldn’t be part of it because he’s not a lawyer.

I think that’s one of his problems. I’ve always said that I don’t think Bush understands the Constitution. He doesn’t seem to know anything about it.

You’d hope that someone around him would have that kind of knowledge. I have hopes that at night his wife is saying, "George, don’t do that, please don’t do that." But I guess he goes ahead and does it anyway.

Let’s consider a scenario: If the 9/11 attacks had happened when Bill Clinton, the master politician, was president, don’t you think he’d be banging the war drums? After all, legislation that he put through when he was president was the blueprint for the USA Patriot Act.

I don’t know. I imagine he would’ve behaved in many of the same ways that President Bush has. I think that almost any president would have. But I wonder if he’d have this obsession with Iraq. I don’t think he would have, but we’ll never know.

He had other obsessions.

Yes, he did.

From a very early age, children are taught that America is the melting pot where all races and groups become one big conglomerate. Was there a conscious time in history when you and other African Americans said, "We’re not going to be part of the melting pot. We’re not going to be whatever this melting pot is. We’re going to be a distinct minority. We’re going to be different"? And, if so, was it the way to go? Did it cause division?

No, I don’t think there was a time when people said precisely that. I think there was a time when people said, "We can do what other groups have done. We can be a part of the whole but also distinct. We can be like Italian Americans, celebrate Columbus Day and still be proud of being Americans. We can be like Irish Americans, celebrate St. Patrick’s Day and still be proud of being Americans. We can have Kwanzaa, for example—a literally made-up Christmas season holiday—we can celebrate that and still be part of the United States." In the 1970s, that feeling became dominant. It doesn’t suggest to me a separation from the whole but a distinction, as is true with every other ethnic or immigrant group in the country. And it’s quite fine for them to do it, and it ought to be quite fine for African Americans to do it.

You’re now considered to be part of the old guard. As a consequence, some young black commentators have criticized you and your participation in your television show, America’s Black Forum.

Yes.

Do you feel like the young African Americans out there are now saying, "Hey, this guy is not radical anymore. He’s part of the establishment. He has right-wingers on his television show and black conservatives"?

Well, if it were my show, that is, if I owned or exercised management over it, I might be able to give you an answer about it. But I’m just an employee.

You sound like a politician now.

The decisions that my employer makes are the decisions that my employer makes. Sure, you feel people are criticizing you for this reason, for that reason, the other, and you keep hearing these calls to pass the torch.

What torch?

The torch of leadership. But I remember when I was 18, 19, 20 years old that nobody passed the torch to me. I had to reach up and grab it. I had to peel the fingers of the man or the woman who was holding the torch away. I had to take the torch. So if I have a torch of leadership, I’m not passing it to anyone. They have to come get it.

You said this about Martin Luther King: "Remember the man and the hero, not just half the dream." What did you mean by that?

I think that when we remember Martin Luther King, it’s from that magic moment in August of 1963 when he spoke at the March on Washington. But he lived for another five years after that, and he said many, many more things. He became much more radical in his outlook, and his views toward economics changed. He embraced a modified kind of socialism. He began to condemn the United States as a warmonger in Vietnam. So the Martin Luther King who died in 1968 is a very different Martin Luther King from the Martin Luther King who spoke in 1963. And to remember the one and not the other is a tragic mistake.

Martin Luther King, because of all his outspokenness against the war and other things, got a lot of criticism from African American leaders.

Indeed he did. His opposition to the war was tremendously controversial. The organization I head, the NAACP, was critical of him at that time, as were the Urban League and other organizations because they, in part, feared alienating Lyndon Johnson, a pro-civil rights president. King was also criticized because blacks at the time had bought into the racist notion that African Americans could have opinions about civil rights but couldn’t have opinions about anything else.

Wasn’t Martin Luther King a man of the people, whatever their color?

Martin Luther King was a universal leader. He wasn’t an African American leading other African Americans. He was a universalist. He believed in the common humanity of all, really a giant, if not the giant, figure of the 20th century.

Do we need a Dr. King type today?

I want to say yes, but I also want to say no because I still see the downside of having the single leader. If Joe Blow becomes the prominent leadership figure in African American life tomorrow morning and then Joe dies of natural causes—a heart attack, for example—where are we? What are we left with? Where do we go now? When is another Joe Blow coming along? So, no. I believe we need prominent figures who can specify what the problems are, what the causes are and what has to be done to eliminate the problems. But I’m not sure we need a single figure.

Has Dr. King’s dream been realized?

No, far from it. It has been partially realized. When he began his public life in ‘55, we lived in a legally apartheid society that ended mostly because of his works in 1964 and 1965. But we still have a society that—if not legally, at least in other ways—is an apartheid society, and we need to move beyond that.

Do you ever foresee a day when America can be colorblind?

Sure, I do. But you can’t just say I’m colorblind and that’s that. And you can’t say, well, we used to have bad color-conscious practices, now we’re going to adopt colorblind practices. Sometimes in order to get beyond color, you have to go to color. A Supreme Court justice said that—I can’t remember which one—but sometimes you have to be color conscious in order to get to colorblindness.

DISCLAIMER: THE VIEWS AND OPINIONS EXPRESSED IN OLDSPEAK ARE NOT NECESSARILY THOSE OF THE RUTHERFORD INSTITUTE.