OldSpeak

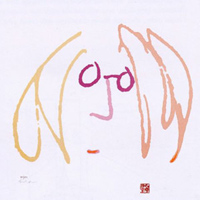

Come Together: The Art of John Lennon

By Jayson Whitehead

May 23, 2007

“Love, love, love... Love, love, love… Love, love, love.” So went the rather simplistic beginning to the Beatles’ “All You Need Is Love.” As a BBC TV camera closed in on John Lennon, bedecked with a tiara of some sort, he followed with a verse that began, “There’s nothing you can do that can’t be done, nothing you can sing that can’t be sung.”

The apotheosis of the appropriately titled Summer of Love, the June 25, 1967 “Our World” telecast was broadcast live to 400 million people worldwide. Of course, it followed the June 1 (June 2 in the United States) release of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, a worldwide happening if there ever was one.

It was a Beatles summer. As kids marched on the Pentagon, they sang “Yellow Submarine” for inspiration: “As we live a life of ease, every one of us is all we need.” The utopian fantasy in practice, the Beatles as patron saints, even Ringo. Especially Ringo! If anything, the Beatles looked like they were having tremendous fun, and whatever they did seemed right.

As the story goes, it all came crashing down rather quickly. “All You Need Is Love” morphed into the all-too-vivid paranoia of “I Am the Walrus” only two months later. By the next summer, the same kids shouting about a submarine were screaming “the whole world is watching” to cameras outside the Democratic Convention in Chicago, where many of them had been beaten by police.

A few months later, the Beatles released the White Album, which inspired a tortured mind to inspire others to kill, scrawling Beatle song titles like “Piggies” on the wall in blood. The next year the Beatles broke up, fragmenting in parts that went off in their own directions.

Lennon went into his own psyche, exploring Primal Scream therapy and releasing Plastic Ono Band, an album that put his mind front and center in songs like “Mother” and “I Found Out.” The same year, he mounted his first art show. In 1969, John had drawn the “Bag One Portfolio” as a wedding gift for Yoko. First published and exhibited in January 1970 at the London Art Gallery, the exhibition, which also included erotic sketches, was raided and closed by Scotland Yard on its second day, with the erotic lithographs confiscated.

Lennon went into his own psyche, exploring Primal Scream therapy and releasing Plastic Ono Band, an album that put his mind front and center in songs like “Mother” and “I Found Out.” The same year, he mounted his first art show. In 1969, John had drawn the “Bag One Portfolio” as a wedding gift for Yoko. First published and exhibited in January 1970 at the London Art Gallery, the exhibition, which also included erotic sketches, was raided and closed by Scotland Yard on its second day, with the erotic lithographs confiscated.

A few of the erotic sketches are on view as part of a show of Lennon’s artwork called “Come Together” that is currently traveling the country. A crude drawing of Yoko masturbating was one of those confiscated, and it is honestly nothing more than the naughty type of scrawl teachers across the world catch a kid making every day.

Others, though, are more powerful, like “He Tried to Face Reality,” a rendering of John sitting in a chair atop a cloud floating across a blue sky. Painted in 1979, it seems an admission on Lennon’s part that his head was often in the clouds, for instance, with a song like “Imagine”: “Imagine all the people living life in peace.” It’s a great idea, but look around and it doesn’t seem like it’s going to happen anytime soon.

40 years ago this June, Sgt Pepper’s took hold of a world waiting for a new savior who turned out to be, for a brief time, four guys from Liverpool. Just a few years later, Lennon was debunking the myth in a song called “God”: “I don’t believe in Elvis, I don’t believe in Zimmerman (Dylan), I don’t believe in Beatles!” Lennon’s voice echoed off in the distance, and piano chords crashed into silence. Then he spoke again, “I just believe in me, Yoko and me.”

As the world continues to fetishize the Beatles and their message of love and peace, perhaps it is more prudent to take into account all the efforts the “smart Beatle” put into communicating the need to take action yourself and not rely on others to do it for you, whether it’s the Beatles or a City Councilor. A year after releasing the epochal Plastic Ono Band, Lennon addressed a crowd of 17,000 at a concert to free a political prisoner. “Okay, so flower power didn’t work,” a bespectacled John Lennon, once their messiah, admitted to the crowd. “So what?! We start again.”

DISCLAIMER: THE VIEWS AND OPINIONS EXPRESSED IN OLDSPEAK ARE NOT NECESSARILY THOSE OF THE RUTHERFORD INSTITUTE.