OldSpeak

My Stay at the Paradise Motel: An Interview with John W. Whitehead

By Michael Khavari

August 23, 2011

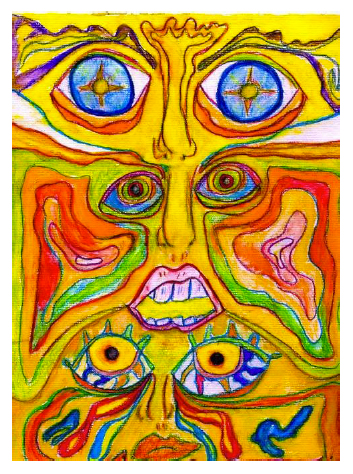

A brief conversation with John W. Whitehead touches on all aspects of life, from politics, to culture, to the human condition. It is apparent that he has thousands of ideas flowing behind his eyes at all times. Such is the case for a man who has lived his life poking the belly of the beast with his words and his work. In addition to being an artist, Whitehead is the founder and president of The Rutherford Institute, a civil liberties advocacy group based in Charlottesville, Va. When he’s not confronting the abuses of the government and corporate America, he’s writing and painting. While he may not have all the answers to life’s questions, Whitehead is certainly trying to figure them out through his work, his art, and his poetry.

One attempt to answer the questions that plague our society can be found in his book, Grasping for the Wind, an investigation into the basis and trajectory of 20th century society. Whitehead also promotes cultural and philosophical discussion through his pop culture magazine, Gadfly, which he launched in 1997 as a print publication and later transitioned to a web magazine. Never one to shy away from a difficult subject, Whitehead is more than willing to discuss the big issues with people from all walks of life. While he never proclaims to know the absolute truth about anything, he always pushes his interlocutors to think about things in a new way. Most recently he took advantage of new opportunities in the world of e-publishing to debut a collection of his poems and paintings entitled Paradise Motel.

I was able to sit down with Whitehead and discuss his latest venture into the creative realms.

Michael Khavari: How long have you been painting and writing?

John W. Whitehead: My earliest poems were written in college. I started writing in college and painting in the early 90s.

MK: What is the inspiration for your painting/poetry?

JW: I draw from everything, but my main inspiration is Francis Bacon. I really like Bacon, but I can’t do Bacon. Just whatever inspires me at the moment. I like all classic painters. As far as poetry goes, my inspirations are Dylan Thomas and T.S. Eliot. In fact, when I was recently in New York, I went to the White Horse Tavern where Dylan Thomas spent his last night drinking. Probably killed himself there. It’s a cool place, they have a portrait of him. You’re at the bar and you look to the left and there he is.

MK: Have you noticed an evolution in your poetry and writing throughout your life?

JW: The poetry has stayed pretty similar, but the painting has changed since I’ve gotten used to the medium. It’s gotten a little better. I’m not a trained artist so I’m not like a Dali, but I can mix colors together and some people like it. Of course, my son Joshua is a good artist. He wasn’t technically trained either, he just started drawing.

MK: I noticed a variety of religious imagery in your poetry. There are many allusions to Biblical stories and images of angels, demons, and God. Is there a particular reason for this or does religion just factor heavily into your worldview?

MK: I noticed a variety of religious imagery in your poetry. There are many allusions to Biblical stories and images of angels, demons, and God. Is there a particular reason for this or does religion just factor heavily into your worldview?

JW: It’s part of my worldview, but I think that any art, in a sense, is an attempt to find meaning in life, which is also a big part of the God thing. Like they say, there’s no such thing as atheists in foxholes, which is probably true. In the end, who knows? But a lot of the religious imagery is me searching and some of it’s subconscious. When I look back at my poetry, I say, “I don’t know where that came from.” One day I sat down and wrote it. Some people would say it’s God-inspired, but I’m not sure I think that human beings are God-inspired. They may be. I think we’re all born with that “search.”

Think of Francis Bacon, a strident atheist who drew the Crucifixion over and over. Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion is one of the greatest paintings of all time. He was fascinated with the Crucifixion, and I think that is a search for meaning.

What gives us meaning? That’s what the poetry is about. We’re finite beings and I think the question is always, “Do we need an infinite reference point to give us coherence and meaning?” That’s the debate between atheists and religious people, no matter what the religion is. What gives us meaning? Most people would say an infinite reference point, whatever that is.

MK: I get the feeling that some of your poetry might be a criticism of organized religion. You have a variety of religious imagery, but some of it could perhaps be considered heretical.

JW: Yeah, obviously some of it is a critique of organized religion, making a statement about it. I think most organized religion misses the point which is people. I think what we’re here for, which I hope came through in some of the poems, is people, one another.

The other thing is there’s just a lot of pain in the world. The Paradise Motel is sort of a parody of modern existence. The question that I ask, which many thinkers ask, religious or not, is, “Where are we at?” That’s the whole idea behind this book of poetry. We’re definitely not in heaven because there’s so many blood and guts spilled every day. So if it ain’t heaven, is it hell? Who knows? I start the book with a Plato quote: “I have heard from the wise that we are now dead and the Body is our tomb.” Well, that may be true. So if it is, we need to be figuring out where we’re at and where we’re headed.

MK: There are many images of imprisonment and entrapment, whether the speaker is trapped physically or in time. Does this feeling of entrapment relate to particular events or is it a general commentary on the human condition?

MK: There are many images of imprisonment and entrapment, whether the speaker is trapped physically or in time. Does this feeling of entrapment relate to particular events or is it a general commentary on the human condition?

JW: I’m talking about the human condition generally because in my work over the years, I’ve dealt with so many people in pain, arrested, jailed and the like. As I said, the carnage that is happening on any particular day—it’s a blood fest. You have animals being killed for meat, human beings in prison, drones flying over countries and killing innocent civilians.

MK: Do you write from your own perspective, or do you attempt to take on the viewpoints of a multitude of people?

JW: Most of the poems are personal. Most decent artwork comes from within. You know, Einstein thought we were basically all mind, that everything was an extension of the mind. I would agree that our bodies are an extension of the mind with all the minds generally connected. That’s being proven daily by work at the University of Virginia and Duke University. There’s a lot of scientists, a lot of universities, studying the issue of whether or not consciousness survives death. And if it does, that changes everybody’s perspective in life.

MK: There are many allusions to loss and insanity among the poems. Are those feelings related to particular life events?

JW: I don’t know how most people keep their sanity in the world today with the disease, the killing, just the general cruelty. What’s presented on television on any given night is cruel. The way we treat other people, attack people, demonize people, how we approach politics and demonize someone running for office. We may not agree with somebody, but should we treat them like they’re the worst thing in the world? I mean, liberals attack Fox News, conservatives attack MSNBC. We’re always attacking one another. I do think there is a certain class of people that run the world that want us fighting, and we do a good job of letting them run the world by fighting with each other all the time over objects and philosophies that in the end mean nothing. They’re just something to fight over.

MK: Does the idea of insanity deal with the feeling of the individual as against the world? It seems that, through your work, you must see the capacity for people to come together and achieve things.

JW: I think you can make very incremental change. There are certain people who make bigger changes like Martin Luther King Jr., Albert Einstein, Mahatma Gandhi, people like that. But that’s only because people follow their viewpoints and try to be like them. So there are certain people that can make changes. I don’t know how much change we can make because if you study history, it doesn’t seem like things are getting better—it seems to be getting worse. The machines that we build today can annihilate whole countries, so I’d say we’re much worse off than we were during the Roman Empire. The other thing is how knowledgeable people are. Between the 24-hour news cycle and the fact that America ranks 11 in literacy, people don’t read books, they can’t think analytically. If I had to compare our time to 1776 or 1642 or whatever, I’d say we’re probably worse off. Right now we’re concerned about Iran getting nuclear weapons when the whole world is getting ready to bomb each other, could annihilate each other. And the environment is under attack now. We’re under attack from every side, so I don’t think things are getting better.

MK: There are a few poems which allude to unnamed females. Are those characters you’ve developed or particular people in your life?

MK: There are a few poems which allude to unnamed females. Are those characters you’ve developed or particular people in your life?

JW: Some of the poems are very biographical about my wife, Carol. Certain people are an inspiration—she was an inspiration. We were together 40 years before she passed away and during that time I would observe her and write about her.

MK: Your poetry invokes the images of bugs and parasites and indicates that evil has infected many aspects of the world. Do you think the world is a generally evil or negative place?

JW: I would agree with the great psychologist Carl Jung that there is an evil force in the world, and it’s personal, whatever it might be. I’ve debated a variety of people on this, and it’s difficult to imagine a Hitler, a Stalin, the maniac running North Korea right now, it’s hard to imagine people doing the things they do. Stoning women, burning women, is that something that people do or something that evil forces do? I think we give too much credit to Hitler and there is something else out there. I would agree that there is a good force. Martin Luther King Jr. said, “The Universe is on the side of justice.” I agree with that, but it’s a long haul. And I’m not sure we’ll ever see justice here on this planet. We may see it somewhere else.

MK: Despite your concerns about evil in the world, in “Evil is Liquid” you imply that evil has an inevitable conclusion. Despite all the terrible things you observe in the world, do you believe that evil must inevitably be conquered?

JW: Again, Martin Luther King said, “The Universe is on the side of justice.” I think it shows through in the small things, the small victories, the Mother Teresas and good people like that, the people that help the homeless, all the good things people do. So, we see there’s good, but will good triumph? I don’t know, but there has to be a source of good as there is a source of evil. I think we have both of them inside of us obviously, but the question goes back to what I said earlier, is there an external evil? I believe that that’s true, but you don’t have to agree with that. Again, I think we give too much credit to the evil people and not enough credit to the good.

MK: What is your writing process like? Do you just scribble things to yourself throughout the day or is there a particular process you go through to get the creative juices flowing?

JW: Sometimes the poems come really fast. And I don’t consider them great poems, but I think some of them are fun poems, fun to read. Some of them come really, really fast. Some of them I’ll labor over them a bit, but most of them come fairly quickly. I don’t spend a lot of time because I think they’re better that way. Eliot and people like that, they strained over their poetry. You can see that in their great epic poems which changed the world. Or the Dylan Thomas poems, you can see he wrote fairly quickly. He wrote in the morning and drank in the afternoon which seemed a good routine for him until it cost him his life. It depends on your writing style. Some people labor over their writing, I don’t like to labor over writing. I just like to see what’s there. And I don’t do a lot of editing on poetry. Most of it comes pretty fast.

MK: Do you prefer to hand write your poetry or type it up? It seems that doing it one or the other would affect your thought process or how you convey the ideas in your head.

MK: Do you prefer to hand write your poetry or type it up? It seems that doing it one or the other would affect your thought process or how you convey the ideas in your head.

JW: I do everything with pen. Some of the poems I did type a little bit, but most are long hand.

MK: Would you consider your poetry writing to be therapeutic?

JW: Writing is therapy. It’s a way to reflect. I’m not sure where it all comes from, but it comes from somewhere. I’m not sure it’s totally human or people it comes from. I just don’t know to be totally honest with you.

MK: Does your poetry inspire your painting or vice versa? Or perhaps a bit of both?

JW: Yeah, the idea of the book was a reflection of that. I talked to my son Josh and I asked him to do a few drawings for the book, he read it and he agreed to do some drawings. All of the paintings were done over a one year period and I noticed that in some of them they made the poetry more fun to read.

MK: Why did you choose to publish in eBook format?

JW: It’s much easier to publish in eBook format. Publishing in the poetry genre is run by academic publishing houses and my poems aren’t quite like Rita Dove’s. I showed the book to some published poets and they said they enjoyed it, but that it would be tough to get it published. Not to mention, the paintings would make the book cost that much more. But with this format, it’s the cost of a hamburger. Plus, if the book gets enough acclaim in the eBook format, people might become interested in publishing it.

JW: It’s much easier to publish in eBook format. Publishing in the poetry genre is run by academic publishing houses and my poems aren’t quite like Rita Dove’s. I showed the book to some published poets and they said they enjoyed it, but that it would be tough to get it published. Not to mention, the paintings would make the book cost that much more. But with this format, it’s the cost of a hamburger. Plus, if the book gets enough acclaim in the eBook format, people might become interested in publishing it.

MK: This book has some level of collaboration with your son. Do you feed off of other people’s creative energy?

JW: Not really, he’s a maverick like me. So, I just said here’s the book, do one for each of the verses and whatever else you want to do. There are a couple others in there that are ones he did that I thought fit well. Plus, his artwork is strange, mine is strange, the poetry is strange, so it just became one strange experience.

MK: What do you hope that readers will take away from your poetry?

JW: What I would like the readers to do is reflect on what’s said in it. Hopefully it would inspire some people to write their own poems, draw their own pictures. I wasn’t trained in literature and I wasn’t trained in art, but I think most people can be artists and most people can be poets. You just have to do it.

DISCLAIMER: THE VIEWS AND OPINIONS EXPRESSED IN OLDSPEAK ARE NOT NECESSARILY THOSE OF THE RUTHERFORD INSTITUTE.