OldSpeak

The President Who Destroyed the Klan: Ulysses S. Grant, An Unappreciated and Undervalued Leader

By Thomas S. Neuberger

March 29, 2013

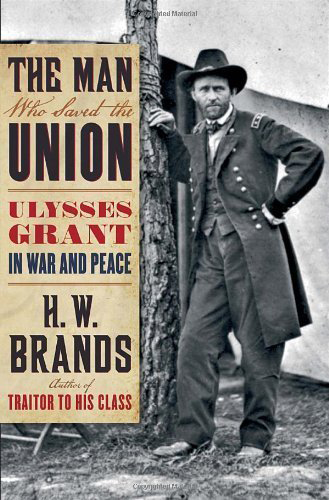

“The Man Who Saved The Union, Ulysses Grant In War And Peace,” by H.W. Brands (Doubleday, 2012). A Review (March 26, 2013):

On the scene in South Carolina federal marshals assisted by army troops rounded up many hundreds of Klansmen and associates. The habeas suspension allowed the arrests to take place far more rapidly than they would have otherwise, because the authorities didn’t have to bring the persons arrested before a judge shortly and charge them with a crime. The effects of the sweep went beyond arrest numbers; many Klansmen fled their home counties ahead of the troops and marshals, some fled the state and a few even fled the country. The detainees overwhelmed the available jails and, after they were eventually indicted, clogged the dockets of the courts.

While President, Ulysses S. Grant destroyed the terrorizing Ku Klux Klan to protect the lives of the freed former slaves. But with the intensely disputed presidential election of 1876 to succeed him in office came the “Compromise of 1877," which gave the White House to the Republican candidate in exchange for the removal of Grant’s federal soldiers from the South and the return of complete control of the region to the racist Southern Democrats. This end of the Reconstruction period enabled the Klan eventually to rise again and to terrorize and murder Blacks until President Lyndon Johnson used the FBI to destroy the Klan a second time, almost 100 years later.

To stop Southern Klan terrorism, President Grant engineered the passage of the Ku Klux Klan Act in 1871, which in professor Brand’s words “remobilized the engines of the Civil War to deal with the Klan and the violence it practiced.” Against strong political opposition, Grant then used his new powers to the fullest to protect the freed slaves, as is described above. Using the words of the author, perhaps this is the epitaph which should have appeared on Grant’s Tomb – “Grant’s campaign put the fear of federal power into the Klan and shattered its sense of impunity. Not for decades would the nightriders exercise such influence again.” To his everlasting honor, President Grant stood for the absolute protection of the freed Black race in the face of Southern Democratic political, social and cultural tyranny.

Thus a careful reading of history should place Ulysses S. Grant in the top twenty percent of American Presidents, a fact that has been withheld from the average citizen who only has heard about a heavy drinking soldier and a scandal or two in his second term in office, scandals which in the 20th Century seemed to be commonplace in a second presidential term. But in this highly readable book professor H.W. Brands has rehabilitated Grant’s presidency, as well as told the exciting story of how he won the peace for President Abraham Lincoln in the face of the Revolution by the Southern States which was the Civil War. We also learn that after his retirement as President he was highly esteemed and acclaimed by Queen Victoria of Britain and her people, Chancellor Otto von Bismarck of Germany, the son of the Chinese Emperor, the Emperor of Japan and leaders of other nations, during a world tour. Such a mark of universal respect is very rare.

Thus a careful reading of history should place Ulysses S. Grant in the top twenty percent of American Presidents, a fact that has been withheld from the average citizen who only has heard about a heavy drinking soldier and a scandal or two in his second term in office, scandals which in the 20th Century seemed to be commonplace in a second presidential term. But in this highly readable book professor H.W. Brands has rehabilitated Grant’s presidency, as well as told the exciting story of how he won the peace for President Abraham Lincoln in the face of the Revolution by the Southern States which was the Civil War. We also learn that after his retirement as President he was highly esteemed and acclaimed by Queen Victoria of Britain and her people, Chancellor Otto von Bismarck of Germany, the son of the Chinese Emperor, the Emperor of Japan and leaders of other nations, during a world tour. Such a mark of universal respect is very rare.

President Grant’s policies also were most enlightened concerning the genocide of the American Indian, which Johnny Cash lamented in his “Bitter Tears” album, in songs like “As Long As The Grass Shall Grow” and “Apache Tears.” Even before he became President, just after the Civil War ended, Grant inherited the Plains Indian War with Sioux Indian Chief Red Cloud and his first lieutenant Crazy Horse. Here he then urged retreat from indefensible settlements and negotiations with the Indians, which resulted in a peace treaty with Red Cloud. When later in office his efforts to help the Indian tribes were admirable, but always ran up against the continuation of the White man’s ceaseless record of murder, outrage, robbery and wrongs, to quote the author. To circumvent the power of the corrupt Indian Bureau and its political allies, he followed a peace policy and tried to put the Society of Friends, known as the Quakers, in place to staff about half of the western agencies dealing with the Indian tribes. In Grant’s words, “wars of extermination . . . are demoralizing and wicked. Our superiority in strength . . . should make us lenient toward the Indian. The wrong inflicted upon him should be taken into account and the balance placed to his credit.” Unfortunately, the western settlers were always the “wild card” in the President’s peace efforts with the Indians. Rumors of gold in the Black Hills of the Dakotas and other pressures lead to the dispatch of the Seventh Calvary to the Yellowstone Valley where a politically ambitious prima donna soldier, George Custer, had his command decimated at the Little Big Horn by Chief Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse. Ever the master professional soldier, Grant had little respect for Custer – “I regard Custer’s massacre as a sacrifice of troops, brought on by Custer himself, that was wholly unnecessary, wholly unnecessary,” he said to the press. But in the media, due to the Custer “massacre,” Grant’s peace policy had failed.

Grant additionally unsuccessfully tried to accept the invitation of the Dominican Republic to peacefully annex it as part of the United States, as had been done with Texas, and thereby govern the Spanish speaking half of the second largest island in the West Indies, just South and East of Cuba in the Caribbean. Most importantly, he saw this as a step towards further eradicating slavery in the Americas which still remained in Cuba and Brazil, perhaps as a partner in Lincoln’s legacy. In his own words, “[m]ore than 70 percent of the exports of Cuba and a large percentage of the exports of Brazil are to the United States . . . Upon every pound [of sugar and coffee] we receive from them an export duty is charged to support slavery . . . Get San Domingo and this will all be changed” because he saw this land as “an island of unequaled fertility,” where sugar and coffee would be cultivated. “With the acquisition . . . the two great necessities in every family, sugar and coffee, would be cheapened by nearly one half.” Thus the acquisition would help ease the race problem that would haunt the U.S. for the next 100 years. “The present difficulty in bringing all parts of the United States to a happy unity and love of country grows out of the prejudice to color,” he wrote. “The prejudice is a senseless one, but it exists. The colored man cannot be spared until his place is supplied, but with a refuge like San Domingo his worth here would soon be discovered, and he would soon receive such recognition as to induce him to stay; or if Providence designed that the two races should not live together, he would find a home in the Antilles.”

Grant additionally unsuccessfully tried to accept the invitation of the Dominican Republic to peacefully annex it as part of the United States, as had been done with Texas, and thereby govern the Spanish speaking half of the second largest island in the West Indies, just South and East of Cuba in the Caribbean. Most importantly, he saw this as a step towards further eradicating slavery in the Americas which still remained in Cuba and Brazil, perhaps as a partner in Lincoln’s legacy. In his own words, “[m]ore than 70 percent of the exports of Cuba and a large percentage of the exports of Brazil are to the United States . . . Upon every pound [of sugar and coffee] we receive from them an export duty is charged to support slavery . . . Get San Domingo and this will all be changed” because he saw this land as “an island of unequaled fertility,” where sugar and coffee would be cultivated. “With the acquisition . . . the two great necessities in every family, sugar and coffee, would be cheapened by nearly one half.” Thus the acquisition would help ease the race problem that would haunt the U.S. for the next 100 years. “The present difficulty in bringing all parts of the United States to a happy unity and love of country grows out of the prejudice to color,” he wrote. “The prejudice is a senseless one, but it exists. The colored man cannot be spared until his place is supplied, but with a refuge like San Domingo his worth here would soon be discovered, and he would soon receive such recognition as to induce him to stay; or if Providence designed that the two races should not live together, he would find a home in the Antilles.”

The strategic interest of such Caribbean outposts also would become self evident later with U.S. possessions, such as Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and other ports purchased by or leased to the U.S. during World Wars I and II. Grant’s vision here was strategic. He called San Domingo “the gate to the Caribbean Sea, and in the line of transit to the Isthmus of” Panama, whose importance President Theodore Roosevelt magnified by constructing the Panama Canal. Here he wished to neutralize Britain’s advantage in this Southern Sea and to put the world on notice of American power which had come of age with the Civil War.

Finally, through the use of Grant’s own orders, letters and words throughout, this compelling biography gives us a full measure of the intellectual power which was in the mind of General and President Grant. There were no speech writers on the battlefield in the Civil War and, I suspect, few in the White House later. The facility of speech, vocabulary and breadth of knowledge evidenced in these original documents are a tribute to the educational system of the 19th Century as contrasted to today, when people just do not write or speak with the ease and eloquence evidenced by President Grant.

Professor Brands’ book proves that Ulysses S. Grant was a President to be admired, despite Southern revisionist history attacking him which was planted in our culture after it lost the Civil War.

DISCLAIMER: THE VIEWS AND OPINIONS EXPRESSED IN OLDSPEAK

ARE NOT NECESSARILY THOSE OF THE RUTHERFORD INSTITUTE.