OldSpeak

What It Means To Be a Soldier: Do Military-Themed Video Games Create a Disconnect Between the Real and the Virtual?

By Neal Shaffer

December 23, 2002

For all of the amazing technological advances of the past fifteen years, it’s not really an overstatement to say that the emergence of the video game is as important as any of them. In May, 1972, when Magnavox released the first commercially available home video game system (Odyssey), there could have been no way to predict the eventual capabilities and significance of the technology. Anybody who has spent any time playing video games can attest to just how captivating they are. Not only are they a great diversion, there’s a god-factor that can’t be ignored. Every game is a unique world, and with enough practice they can all be mastered.

|

So while more traditional entertainment industries such as film, television, and music are struggling with iffy sales, video games continue to grow. Including both home consoles and PC-based games, 2001 sales in the U.S. alone totaled 6.35 billion dollars (according to a study by the Interactive Digital Software Association). This is to say nothing of the highly lucrative Japanese market and the various European markets. The numbers have increased every year, and it’s safe to say that 2002 sales will continue that trend.

As large as the numbers are, it’s not all that difficult to see why. Other forms of entertainment media are generally passive. After the initial exposure the consumer has seen or heard everything there is. We can see in this one reason for the relatively sudden success of DVD’s: added features such as commentary, deleted scenes, trailers, etc., add to the experience and make a secondary investment worthwhile. The same thing happens to a lesser extent with CD’s. CD-ROM features and Internet links give the buyer added value on the initial purchase of the music. It’s probably true that in this dynamic lies a sad commentary on the state of the culture, but it is what it is. Modern consumers tend to gravitate their entertainment dollar toward experiences and not toward works. Not everybody can see the value of listening to a great album or watching a great film over and over again, finding a new perspective and nuance each time (most of the top sellers don’t lend themselves to that anyway). Even when possible, such a process demands too much effort, where video games demand just enough.

These facts are not lost on pundits, and recent years have seen a great deal of ink wasted on the supposedly nefarious aspects of video games. The criticism has generally focused on the matter of violence and how repeated exposure to it has warped the minds of America’s youth. It’s a critique as old as media itself, and it ignores the basic fact that people who do things according to suggestion had to be open to doing them in the first place–it can’t be stated enough that a correlation is not a cause. Having said that, there may be something to the notion of video games having a profound social importance, but it’s not the connection one might expect.

One of the major casualties of the United States’ "War on Terror" is meaning. Academic theorists have been pointing out various ways in which this culture has lost touch with meaning for years, but this epoch is the first in which that process is a matter of official policy. Ari Fleischer has never uttered a true word in his life, and yet it is his mouth that gives voice to some of our most important national policies. On one level it’s drop-dead hilarious to listen to, and watch, him speak. That laughter, however, is as uncomfortable as it is legitimate. It’s the sort of half-laughter that you can’t help but indulge when one of your friends utters a particularly inappropriate joke. In the case of our Presidential Spokesman, there’s no chance to pull him aside later for a reprimand.

Video games are one place where meaning endures. At the start you are given your character, your control, your parameters, and your mission. The best games afford several different options for each of these, and the cream of the crop (games such as the wildly popular Grand Theft Auto series) allow you to dabble around in the virtual world for as long as you like before attempting a mission. But the common thread is purpose, and it doesn’t take long to become your character. Many of the most popular video game titles are "First Person Shooter’s," or FPS’s. These are the games where you control one character and the object is to move through the virtual world deploying various armaments to destroy your enemy. It is FPS’s that have garnered the most attention from the concerned parent crowd. While they fall generally into the category of harmless escapism, a trend has developed that should be raising alarms.

|

The simulation of military operations has been a staple of game play forever (chess, anyone?) and has been an integral part of the development of video games. That, too, is harmless to a point. But if there is anything to the critique of video games as senselessly violent it is that they do tend to alter a player’s perception of activity. It’s hard to spend two or three hours controlling reality one way and then forget it as soon as the power is turned off. When the gameplay is abstract it tends not to matter. Anybody that can’t separate the destruction of zombies or Russian spies from reality is a fool to begin with. But what if the gameplay is tied directly to real activity?

Two recently released games in particular raise the eyebrows: Tom Clancy’s Splinter Cell from UbiSoft and Conflict: Operation Desert Storm from Gotham Games. In the former you are controlling a "Splinter Cell," a nameless NSA operative whose job it is to (verbatim from the game’s website) "Infiltrate terrorists' positions, acquire critical intelligence by any means necessary, execute with extreme prejudice, and exit without a trace!" In the latter you are in control of a squadron of either U.S. or British Special Forces (your pick) on a variety of missions in Iraq during the first Gulf War. The advertising tagline for this game is "All Americans pledge allegiance. A select few show it." Does any of this sound familiar?

|

Propaganda is so ubiquitous that pointing it out sometimes seems obvious, and it would be impossible to allege or prove that the government had anything to do with the development of these games. Their existence (and, indeed, the existence of several other military games whose currency is somewhat suspect) must be chalked up to unfortunate coincidence. Still, there’s something strange about it. Given the video game industry’s incredible economic hold on the American populace, is it appropriate for developers to tie their wares so directly to the current political climate? Especially since the quality of the gameplay is not changed by the story line attached to it, and especially since the politics of the current administration are so blatantly jingoistic? By way of example, one of the more popular current titles is EA’s Medal of Honor series. In it you are in control of a WWII soldier. The gameplay is excellent and the politics are not overbearing. Then there are games like Microsoft’s Halo (generally acknowledged as one of the best FPS’s ever) where the battle takes place in a futuristic environment. So why these games, and why now?

There is neither a need nor a way to address the developers of these games and accuse them of some kind of wrongdoing. Their games are moneymaking devices, and at this they succeed admirably. But they reflect something about the culture (ours) to which they’re sold in the same way that the most popular Japanese titles, many of which aren’t even available here, reveal something about Japanese culture and values. They both reflect and, on the back end, shape our values. At what point does the distinction become clear? At Americasarmy.com.

|

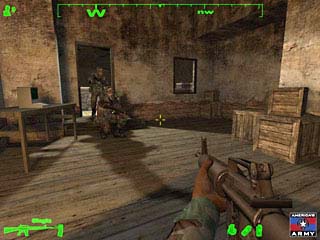

America’s Army is a "thrilling first-person action game" that carries the tag line "Empower yourself. Defend freedom." It was created and developed by the U.S. Army and is available for free download and play to anyone who wishes to do so. It is technologically and graphically on par with most of the games that are commercially available. What it amounts to is an attempt by the government to harness the latent energy of a generation of apathetic youth via the means of electronic propaganda. You can have the same fun that costs $50 at Best Buy for free, and learn something in the process.

What you learn is the government’s version of what it means to be a soldier. Players of the game must go through all aspects of basic training before entering the online combat mode. Any violation of "Army Values" or the "Rules of Engagement" results in a loss of "Honor Points" that can land you in the brig. It is essentially an intentional version of what games like Splinter Cell and Desert Storm already are: a chance to experience the thrills and challenges of combat with none of the risk. While commercially available games can be excused to some extent since they’re not technically supposed to be anything other than entertaining, how do we excuse the government?

|

The short answer is, we can’t. But that’s all right, since they do a hell of a job digging their own grave in an attempt to excuse themselves. The FAQ for the game, designed for parents (everything, after all, is for the children), is an astoundingly comprehensive study in doublespeak. It’s too rich and extensive to elucidate here (the entire thing is available at http://americasarmy.com/faq.php?section=Parents#parents1), but what it essentially says is that the Army hopes to recruit capable youngsters by speaking their language, all the while remaining careful not to offend soccer moms. Kids today love games, so let’s give ‘em a game.

The problem, of course, is that the Army is no game. The website admits as much between the lines, but that’s obviously not their focus. We have a basic problem: the culture is moving increasingly toward a disconnect between real and virtual experience, and a blurring of perception between the two. The commercial video game industry has reached a very high level of success by both acknowledging and contributing to it. Now the government is attempting to harness it. So what happens when some pimply-faced 14-year-old decides that the Army game is cool and signs up the day he turns 18? The Army admits that the game exists to "substitute virtual experiences for vicarious insights. It does this in an engaging format that takes advantage of young adults' broad use of the Internet for research and communication and their interest in games for entertainment and exploration." But it does nothing to prepare potential recruits for the reality that military life means giving up your independence and freedom; that some masochistic drill instructor is happier humiliating you than he is teaching you; that your job is to put aside any rational or intellectual thought and kill on command.

|

Now, don’t get confused. America needs soldiers the same way any other nation does. The time may very well come (though it certainly will not come under the stewardship of Bush, Rumsfeld, et al.) that we have a just war to fight. When we do, we will need dedicated, talented, and trained soldiers to fight it. But in the meantime, what we have is a surreptitious campaign to convince young people that war is something it isn’t and that military service is something it isn’t. No matter how good the Army’s intentions may be (and they may very well be good), choosing the video game as a means of seduction is misguided. The virtual world is a poor substitute for the real one, and it always will be. Choosing to indulge the fantasy is up to us, but when the government sells us that fantasy we have to seriously question where we are, how we got here, and just where we might be going.

DISCLAIMER: THE VIEWS AND OPINIONS EXPRESSED IN OLDSPEAK ARE NOT NECESSARILY THOSE OF THE RUTHERFORD INSTITUTE.